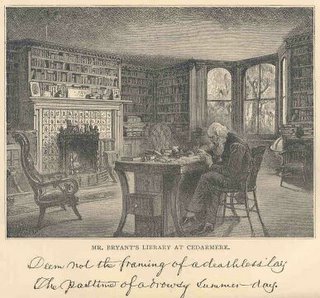

*Ink impression of Bryant in his library at Cedarmere, from my (now restored) copy of Homes and Haunts of our Elder Poets, D. Appleton & Co, 1881.

Today is the birdthday of William Cullen Bryant, born in 1794 in Massachusetts. He is categorized as part of the New England Renaissance...a pre-transcendentalist. His father recognized William's literary gift early in life, and encouraged his son along the way. At ten years of age he made very credible translations from some of the Latin poets. By the age of Thirty, he moved to New York City, to pursue a career in law and journalism. Within four years, he became editor-in-chief and part owner of the New York Evening Post, a position which he helf for almost fifty years.

Some of his most well-known works of poetry are: Thanatopsis, To a Waterfowl, and perhaps To The Fringed Gentian. My Autumn Walk is an interesting poem, where he remembers American soldiers fighting while he enjoys his autumn walk.

Here is a stunning tidbit I stumbled upon while reading about him in one of the books on our shelf called Treasures in American Literature. His essay is called "Sensitveness to Foreign Opinion" (1839).

"...we seize the occasion to protest against this excessive sensibility to the opinion of other nations. It is no matter what they think of us. We constitute a community large enough to form a great moral tribunal for the trial of any question which may arise among ourselves. There is no occasion for this perpetual appeal to the opinions Europe. We are competent to apply the rules of right and wrong boldly and firmly, without asking in what light the superior judgement of the Old World may regard our decisions.

...If an American author publishes a book, we are eager to know how it is received abroad, that we may know how to judge it ourselves. So far has this humor been carried that we have seen an extract, from a thrid- or fourth-rate critical work in England, condemning some American work, copied into all our newspapers one after another, as if it determined the character of the work beyond appeal or question.

...If every man who writes a book, instead of asking himself the question what good it will do at home, were first held to inquire what notions it conveys of Americans to persons abroad, we should pull the sinews out of our literature. There is much want of free-speaking as things stand at present, but this rule will abolish it altogether. It is bad enough to stand in fear of public opinion at home, but, if we are to superadd the fear of public opinion abroad, we submit to a double despotism. Great reformers, preachers of righteousness, eminent satirists in different ages of the world--did they, before entering on the work they were appointed to do, ask what other nations might think of their countrymen if they gave utterance to the voice of salutary reproof?"

Wow! What do you all think?

No comments:

Post a Comment